You’ve probably come across the acronym RAID before (maybe in SSD/HDD specs, NAS configuration menus, BIOS settings, or even in discussions). It looks technical, it sounds complicated, and for many people it feels like something only IT departments should worry about.

But what is a RAID array? A RAID array (short for Redundant Array of Independent Disks) is a way of combining two or more drives so they act as one system. Depending on the RAID level, this setup can improve speed, increase storage reliability, or do both at the same time. That’s why RAID appears everywhere from home NAS units to professional servers: it gives users a way to protect data and keep systems running even when one drive fails.

History of RAID

We could stop at a simple RAID array definition, but this site isn’t about quick dictionary entries, so it makes sense to walk through how RAID actually came to be and why it changed storage forever.

The story goes back to the late 1980s, when hard drives were slow, expensive, and far less reliable than what we use today. A group of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley (David Patterson, Garth Gibson, and Randy Katz) started looking for a way to squeeze more performance and reliability out of consumer-grade disks without buying proprietary, high-end hardware. Their 1988 paper, “A Case for Redundant Arrays of Inexpensive Disks,” introduced the world to the concept we now call RAID.

The idea was pretty bold for the time: instead of relying on one big, costly drive, why not combine several cheaper ones into a single logical unit? By arranging the disks in different patterns (what later became RAID levels), they showed you could boost speed, increase reliability, or balance both depending on the configuration. This approach made large-scale storage far more accessible, especially as personal computers and early servers started demanding more capacity.

Through the 1990s, RAID began showing up in workstations, database servers, and eventually in home systems as hardware prices dropped. By the early 2000s, RAID had split into two worlds: hardware RAID, driven by dedicated controllers in servers, and software RAID, built into operating systems like Windows, Linux, and macOS (more details on this later). Today, RAID remains a core part of storage architecture, but it is no longer cutting-edge research; it’s the everyday backbone of NAS boxes, enterprise servers, and even enthusiast PC builds.

How Does RAID Work?

To understand how a RAID setup actually functions, it helps to break the process down into the basic building blocks. A RAID array is not just “a bunch of disks working together”, it’s a coordinated system of logic, redundancy, and data distribution. Whether it’s inside a NAS, a server, or even a desktop RAID system hard drive configuration, the whole mechanism depends on how the controller handles the core RAID array components.

Here’s what happens under the hood:

- Striping writes pieces of a file across multiple disks. Instead of keeping an entire file on one drive, the RAID controller splits it into blocks and spreads those blocks across the array. Reads and writes then happen in parallel (the disks work together like lanes on a highway – more lanes, more throughput).

- Mirroring creates exact copies of data on paired drives. For levels like RAID 1, the array duplicates data onto two (or more) disks at the same time. If one drive fails, the other still holds a complete copy.

- Parity calculates recovery data alongside the real data. In parity-based arrays (RAID 5, RAID 6, etc.), the system uses a mathematical formula to store extra information that can rebuild missing data if a disk dies. It’s not a full duplicate like mirroring, but it’s enough to reconstruct whatever was lost.

- Rebuilding restores missing data to a replacement disk. When a drive fails in a parity or mirrored setup, the controller pulls information from the surviving disks and reconstructs the contents of the failed one. This rebuilding phase can take hours on large disks, but it’s what prevents data loss in fault-tolerant RAID levels.

- Whether it’s a hardware controller inside a NAS or a software implementation in your OS, the controller decides how data moves, how redundancy works, and how each physical disk participates in the array. It’s the brain of the entire system.

Standard RAID Levels

Now that we’ve walked through how a RAID system works, it makes sense to break down the RAID levels you’ll see most often. Each one mixes disks in a different way, and the results vary from pure speed to full redundancy (or a blend of both). Below are the classic RAID setups:

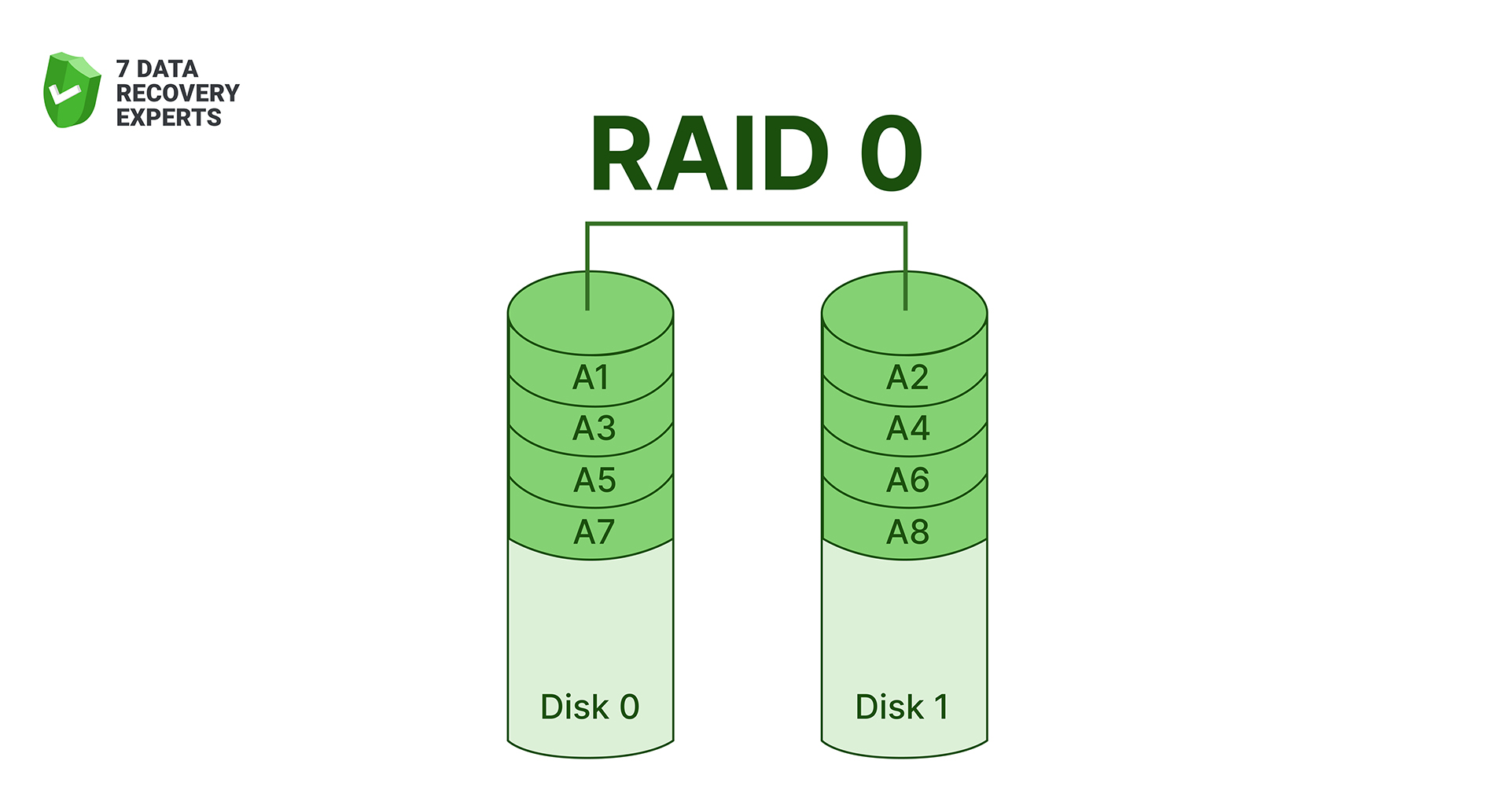

1. RAID 0 (Striping for Speed)

RAID 0 spreads data across two or more drives in alternating blocks. Because the system reads and writes to every disk at once, the performance boost is obvious the moment you push large files through it. There’s a catch, though: RAID 0 offers zero redundancy. If one disk dies, the entire array collapses with it. That’s why RAID 0 is popular with users chasing raw throughput (video editors, gamers, scratch-disk workflows) but never recommended where data safety matters.

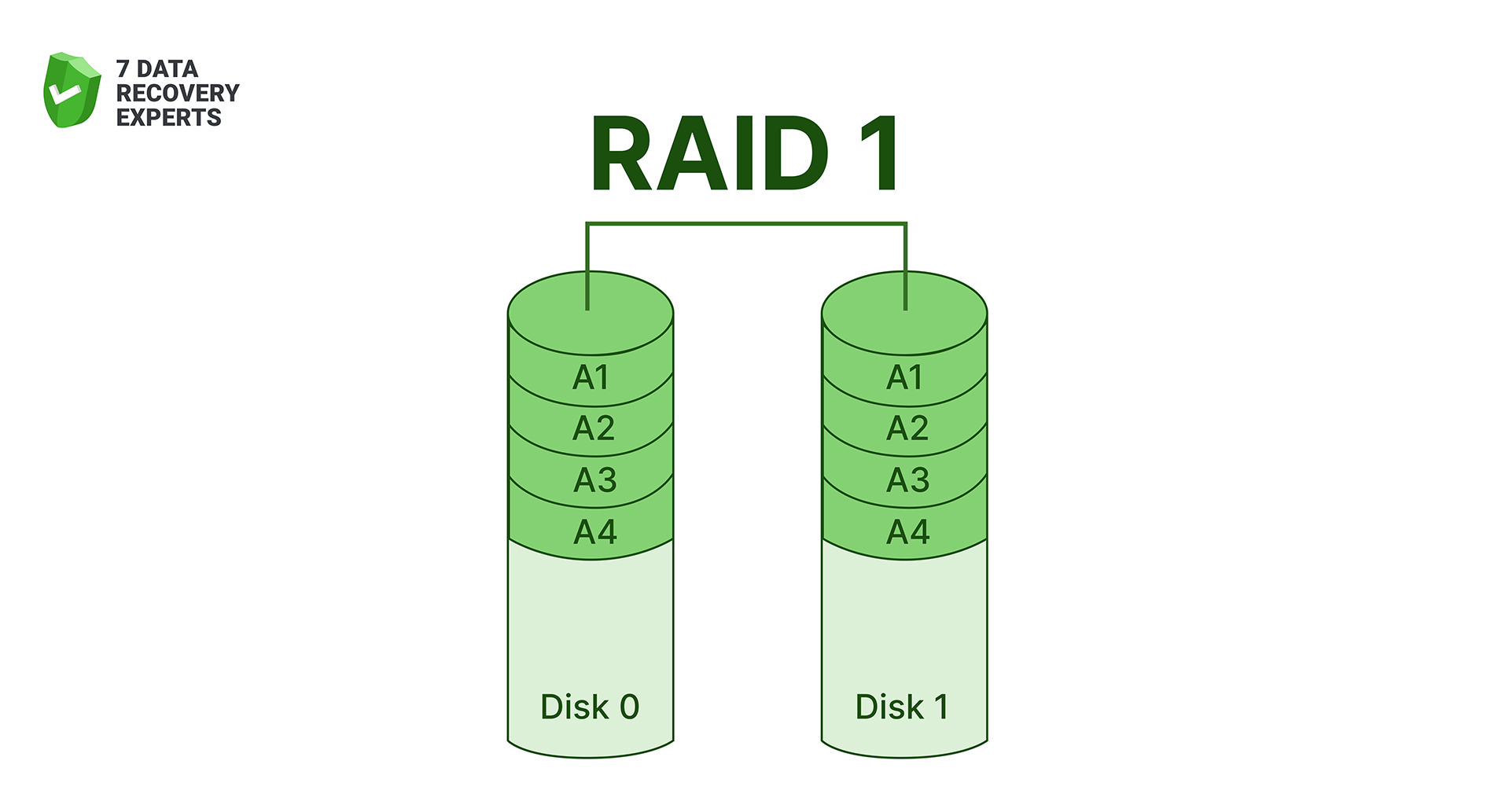

2. RAID 1 (Mirroring for Reliability)

RAID 1 keeps two drives as exact clones of each other. Every write goes to both disks, so if one fails, the array keeps running off the surviving copy. People often choose RAID 1 for small servers, important workstations, or home NAS units where uptime is more important than maximum speed. The trade-off is capacity, as you only get the size of a single drive, no matter how many disks participate.

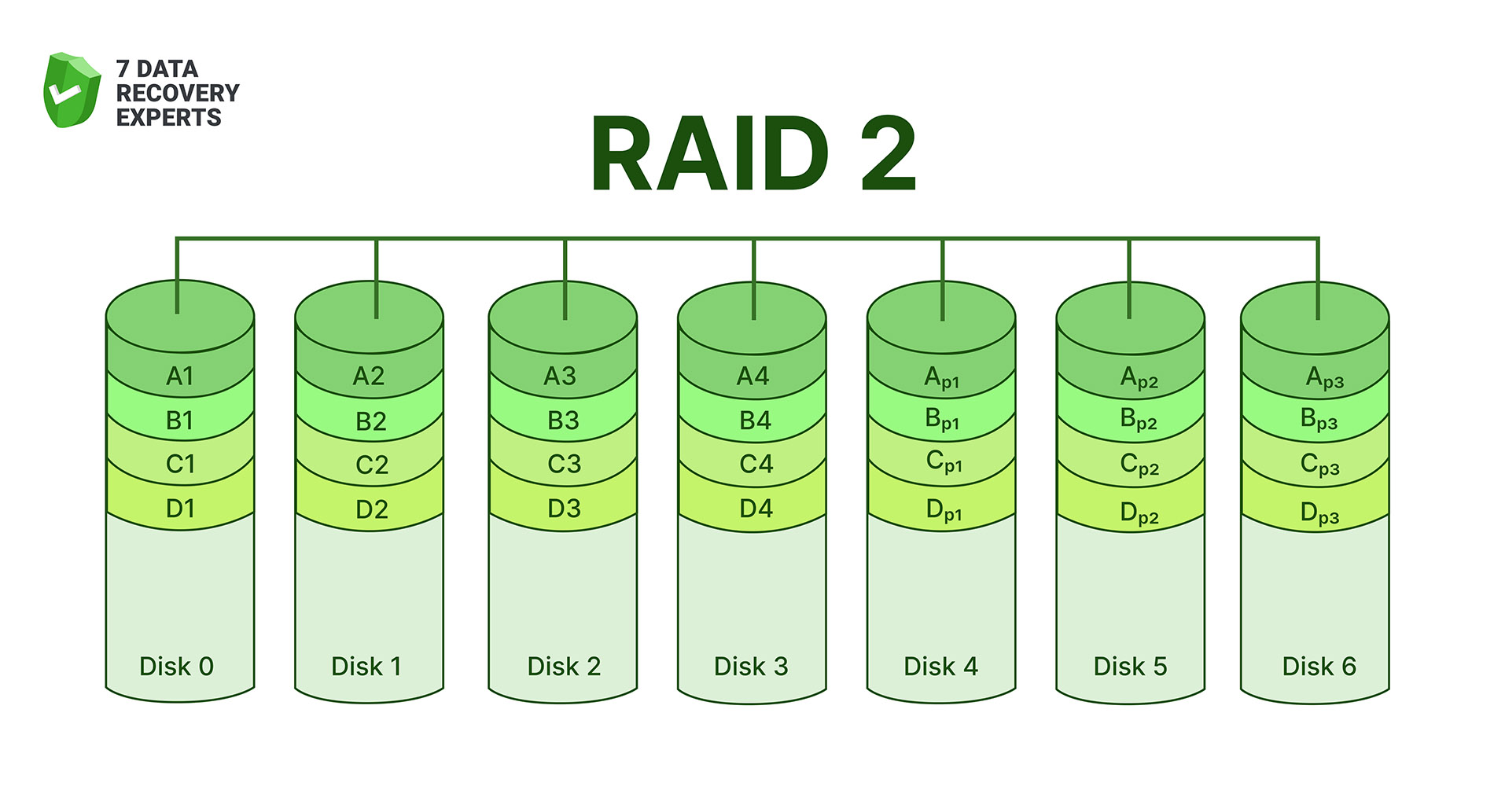

3. RAID 2 (Error-Correcting Striping)

RAID 2 uses a method you almost never see today: it splits data across several disks at the bit level and stores error-correction information on dedicated parity disks. In theory, this design offered strong protection against read/write errors, but in practice it required a synchronized set of drives that all spun at exactly the same speed. That level of hardware coordination made RAID 2 incredibly expensive, so the industry eventually abandoned it once better error-correction methods appeared directly inside hard drives.

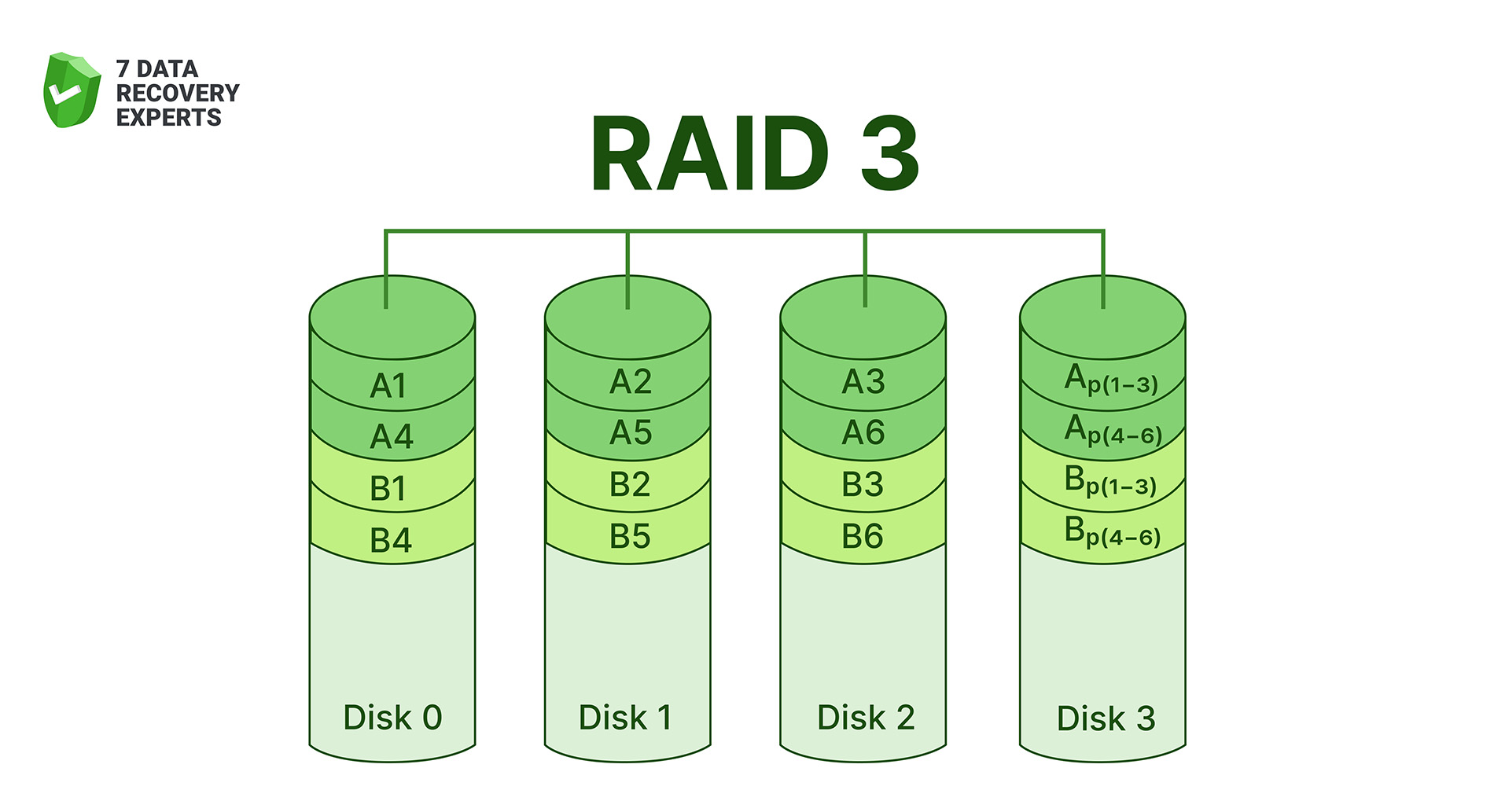

4. RAID 3 (Byte-Level Striping with Dedicated Parity)

RAID 3 stripes data byte-by-byte across the drives, with a single dedicated parity disk handling recovery information. Because data is split so finely, all disks must work in lockstep, making the array great for large sequential reads and writes (video editing systems used it for that reason years ago). But having one parity disk turns it into a bottleneck. Every write requires updating that same parity drive, so performance suffers under mixed workloads. RAID 3 exists mostly as a legacy concept now, replaced by more balanced designs.

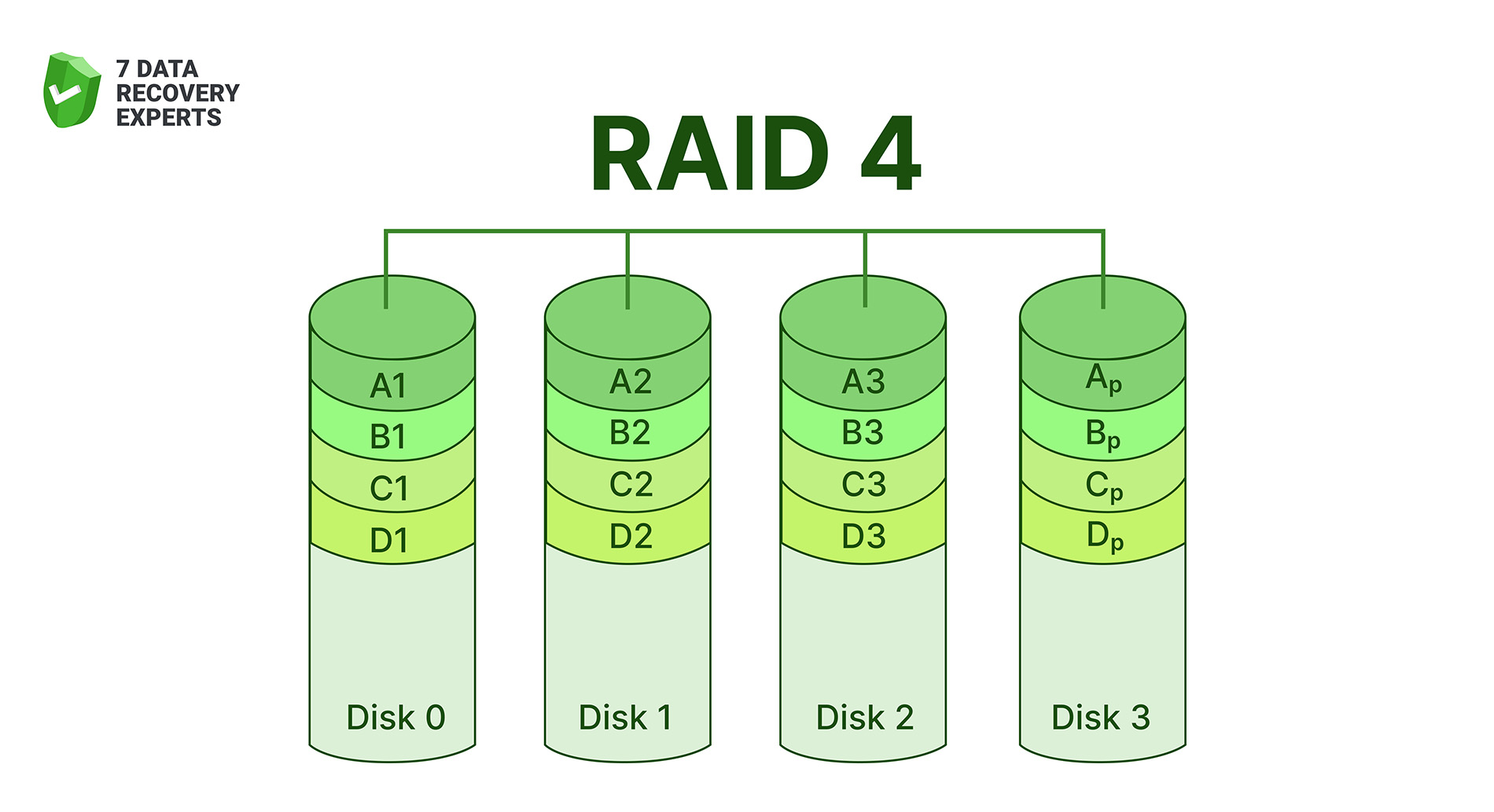

5. RAID 4 (Block-Level Striping with a Dedicated Parity Disk)

RAID 4 solves one RAID 3 limitation by moving from byte-level to block-level striping. That makes reads faster, because the system can pull blocks directly from a single drive without involving the entire array. However, RAID 4 still leans on a single parity disk, which becomes a choke point during heavy writes. Every update touches that parity drive, slowing things down. RAID 5 later fixed this by spreading parity across all disks.

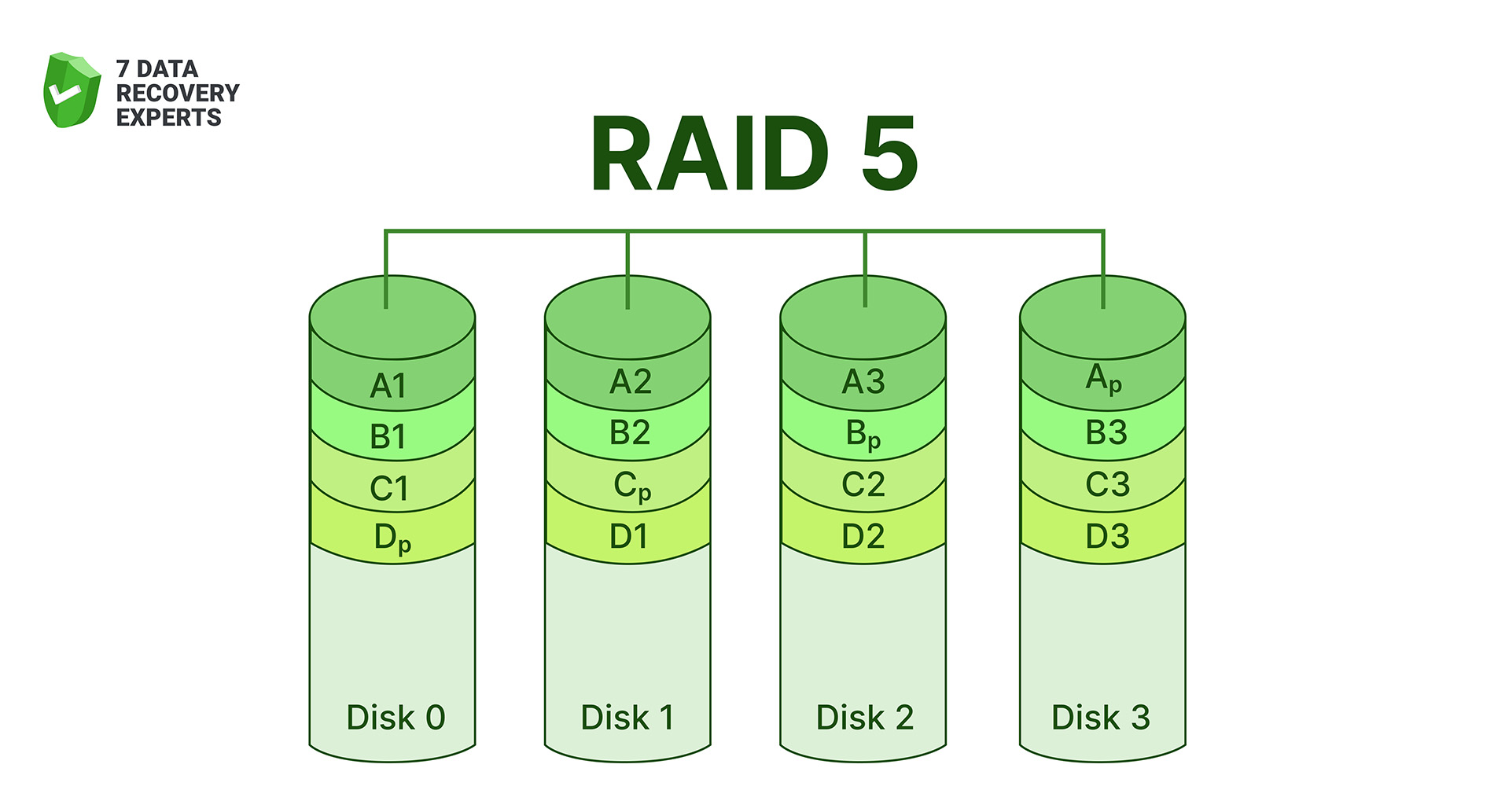

6. RAID 5 (Distributed Parity)

RAID 5 spreads both data and parity information across all drives in the array. That means there’s no single parity disk slowing things down. Reads are quick, writes are decent, and the system can survive one drive failure without losing data. It became one of the most common RAID choices for small businesses and NAS users because it balances performance, capacity, and protection. The trade-off is rebuild time: when a disk fails, restoring the array can take hours (or days on large drives), and performance drops during that process.

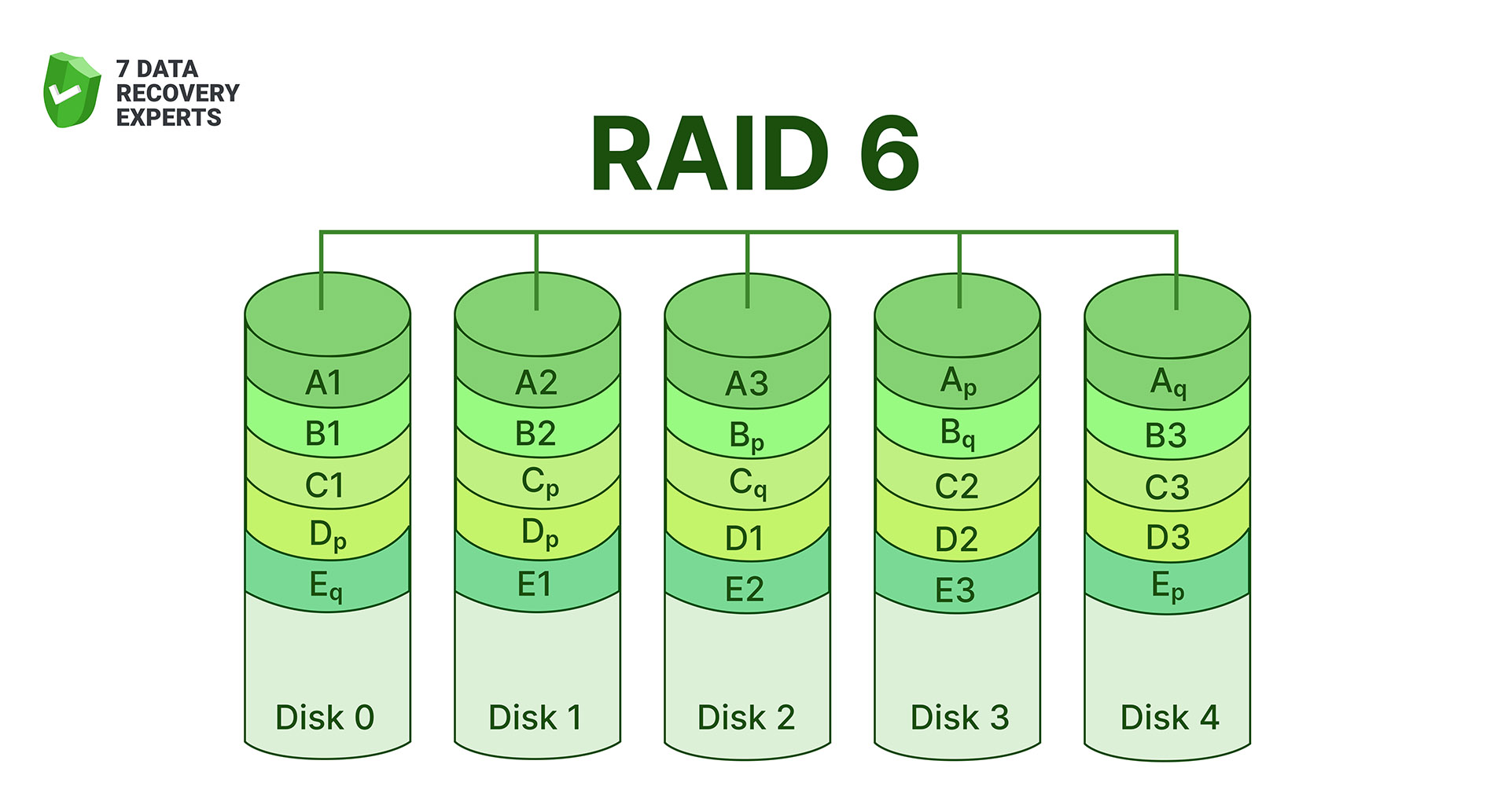

7. RAID 6 (Double Parity for High Fault Tolerance)

RAID 6 takes the RAID 5 idea and strengthens it with a second independent parity block. That means the array can survive two simultaneous disk failures (a huge advantage for large-capacity drives where rebuilds take many hours or even days). The downside is slower write performance compared to RAID 5, since the system must calculate two sets of parity every time data changes.

When you look at the full list of RAID levels, it feels long enough to scare off anyone who isn’t a storage engineer. But in practice, only a few of these setups show up regularly. RAID 0, RAID 1, and RAID 5 dominate most real-world use. Other levels (RAID 2, RAID 3, RAID 4) mostly survive in textbooks and old storage manuals rather than in modern RAID array storage solutions.

Nested (Hybrid) RAID Levels

By now the list of standard RAID levels may feel long enough, but in real-world setups you’ll often see something called nested or hybrid RAID. It’s when you take two RAID levels that solve different problems and combine them so the array inherits the strengths of both. Below are the most common hybrid configurations you’ll run into.

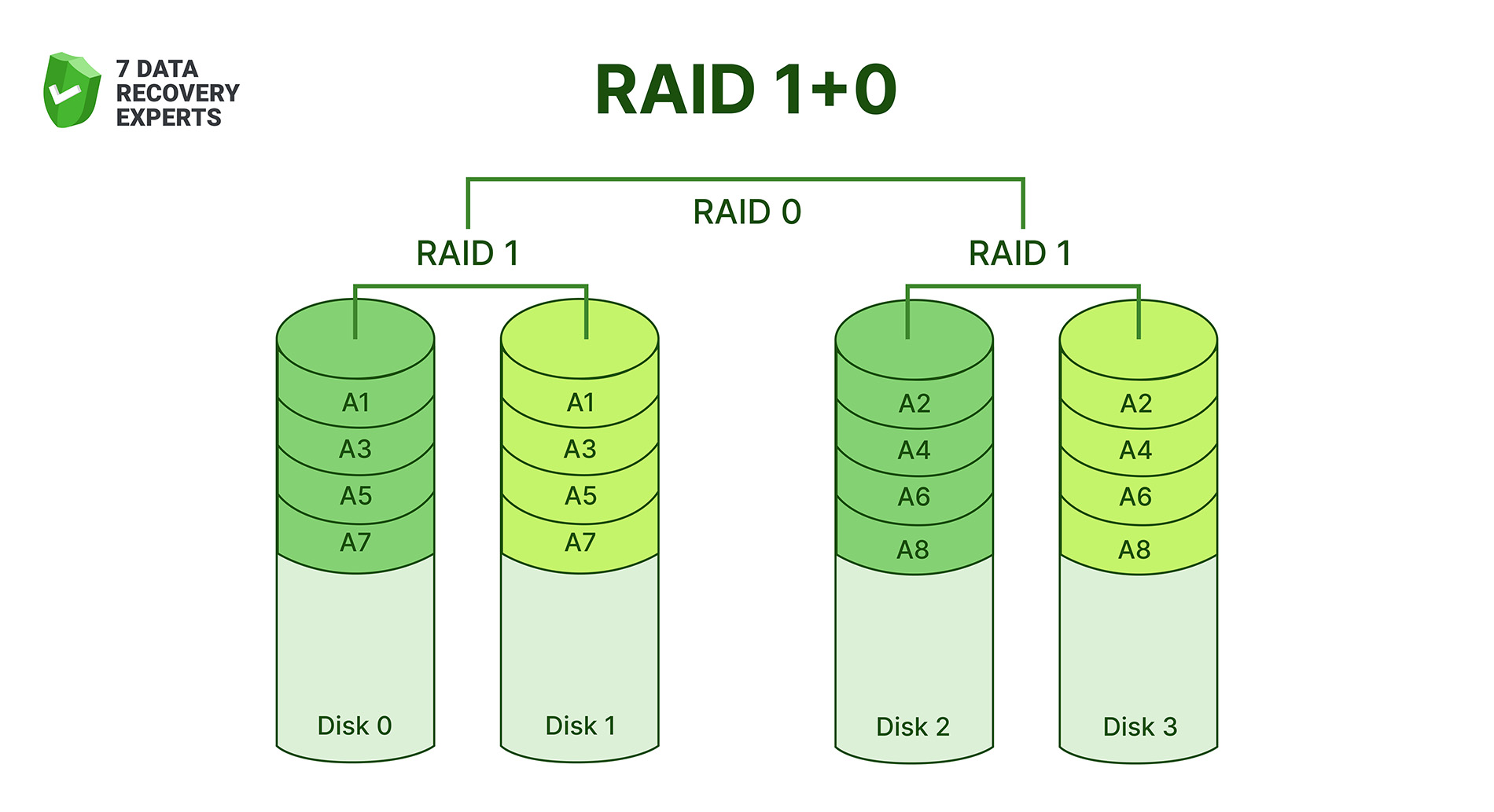

1. RAID 10 (RAID 1+0)

RAID 10 stripes data across mirrored pairs. Each pair acts like RAID 1 (two drives holding the same content), and those pairs are then striped together like RAID 0. The end result is fast performance with the safety of redundancy. RAID 10 needs at least four drives and loses half the total capacity, but it pays off with low latency, quick rebuild times, and excellent overall stability. Most professionals consider RAID 10 the default safe choice for setups where both speed and durability matter.

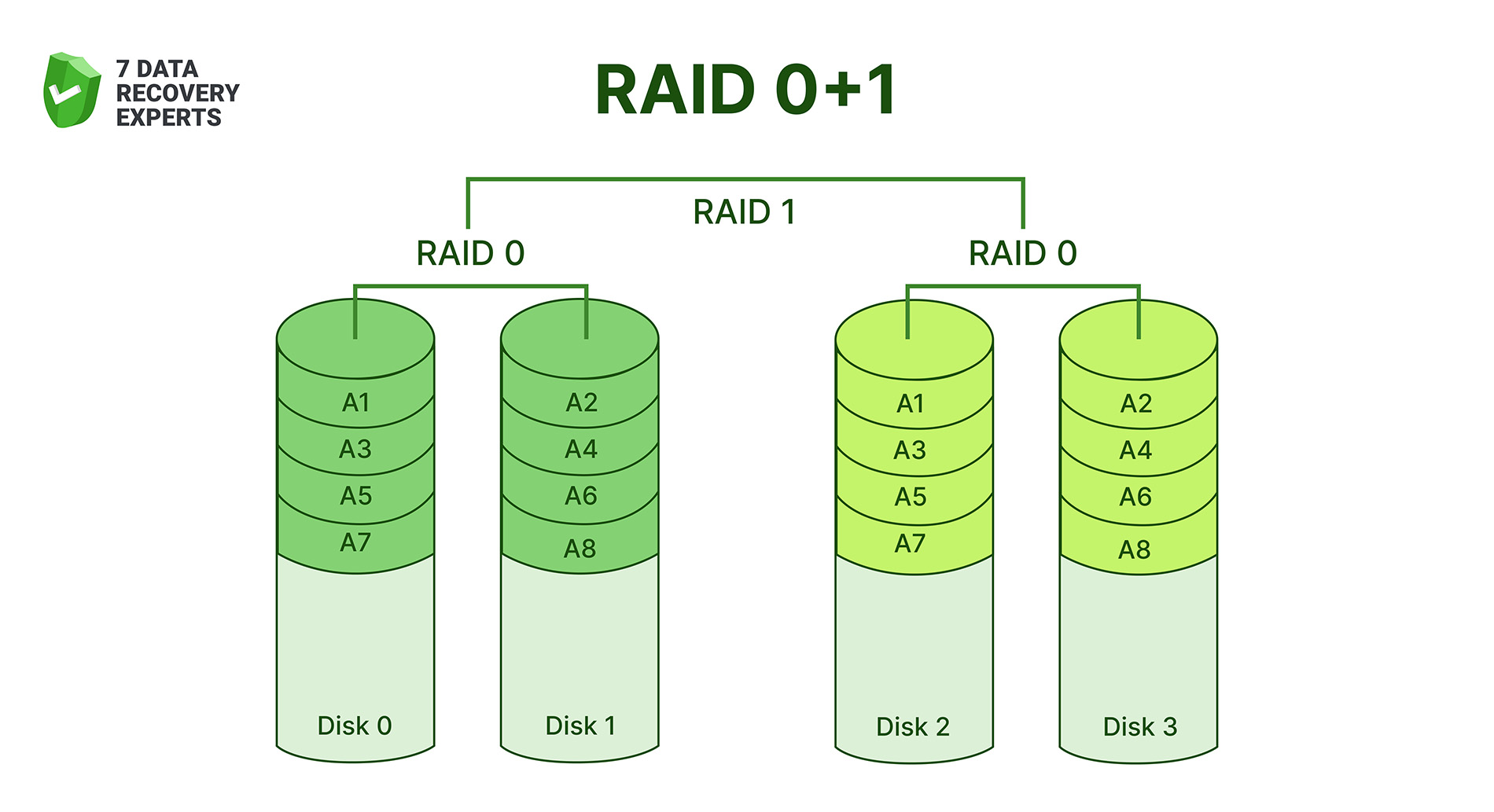

2. RAID 01 (RAID 0+1)

RAID 01 mirrors two RAID 0 arrays. Since the mirroring happens after striping, the structure isn’t as resilient as RAID 10. If a single disk in one stripe set fails, the entire half of the array becomes unusable, leaving only the mirrored copy. You still get good read/write speed because of striping, but RAID 01 is rarely chosen today (RAID 10 does the same job better and with far less risk).

3. RAID 50 (RAID 5+0)

RAID 50 stripes across multiple RAID 5 groups. It combines RAID 5’s parity protection with RAID 0’s speed gain. RAID 50 allows larger arrays, more consistent performance, and better fault tolerance compared to a single RAID 5. Rebuilds are less stressful too, because each RAID 5 group handles only part of the total workload. This layout works well for large file servers and systems that need strong throughput without sacrificing data protection.

4. RAID 60 (RAID 6+0)

RAID 60 is similar to RAID 50, but each group uses RAID 6 parity instead of RAID 5. That means dual-parity protection, which is excellent for environments with large disks and long rebuild times. RAID 60 handles multiple drive failures better and maintains stability even when the array is under heavy load. It’s often chosen for enterprise storage clusters, archival systems, and RAID array storage setups where uptime is critical and the array spans many disks.

You may also see more combinations like RAID 15 (striping across RAID 1 mirrors), RAID 51 (mirroring RAID 5 arrays), or RAID 61 (mirroring RAID 6 arrays). These designs exist mostly in theory or in very specialized enterprise hardware. They behave exactly as you’d expect based on their components, but they require many disks and are rarely used outside high-end engineering or research environments.

Hardware RAID vs. Software RAID

Back when we first talked about the RAID array meaning, we briefly mentioned that RAID can work in two very different forms: hardware-based and software-based. Now it’s time to look at them properly, because the differences matter once you start building or maintaining a RAID disk array.

- Hardware RAID relies on a dedicated controller, either a card installed in the system or a built-in controller inside a NAS or server. This controller handles all RAID logic on its own: parity calculations, striping, mirroring, rebuilds, error correction. The operating system barely gets involved, which usually means faster performance and more reliability, especially under heavy workloads. Hardware RAID shines in professional environments where uptime and throughput actually matter. The downside? Cost. And if the controller itself fails, you often need the same model to rebuild the array.

- Software RAID, on the other hand, lives inside the operating system. Windows, macOS, Linux, and BSD all include tools that let you create RAID arrays without extra hardware. Performance depends on your CPU, but for many home users and small offices, software RAID works perfectly fine. It’s flexible, cheap, and easy to monitor. The catch is that advanced features (caching, battery-backed write protection, smarter rebuild logic) aren’t always available, and CPU load can increase under heavy activity.

In simple terms, hardware RAID is the muscle, software RAID is the convenience. And the right choice depends on your budget, your workload, and how critical the array is.

Benefits of RAID

RAID exists for one simple reason: a single drive is rarely enough. Whether we’re talking about speed, reliability, or keeping downtime to a minimum, combining drives into a RAID disk array solves problems that a lone hard drive (or SSD) can’t.

- The biggest advantage is redundancy. In RAID levels like 1, 5, 6, or 10, the array keeps running even if one (or sometimes two) disks die. Your data stays accessible, and the system doesn’t collapse instantly.

- Another practical benefit is speed. RAID 0, RAID 10, and RAID 5 (to a degree) improve performance because they spread data across multiple disks. Reads and writes finish faster, which helps with large files, editing work, virtualization, and any workload that stresses storage.

- RAID also offers bigger usable storage by merging multiple physical disks into one logical unit. Instead of juggling separate drives, the system treats the entire RAID set as a single space, making management simpler and cleaner.

- And finally, RAID improves recovery chances. If a drive fails inside a redundant RAID level, you can rebuild the array and keep everything intact. It’s not a backup, but it definitely buys time and prevents instant data loss.

Disadvantages of RAID

Of course, RAID isn’t perfect, and even though it solves a lot of storage problems, it brings a few of its own:

- Every RAID setup depends on multiple disks working together. The more drives you add, the greater the probability that at least one of them fails.

- A RAID array protects against hardware failure, not accidental deletion, malware, corruption, or a full array collapse. Many users assume RAID is a backup system, which leads to risky setups.

- When a drive fails in RAID 5 or RAID 6, the array needs to rebuild itself. On today’s multi-terabyte drives, that process can take many hours — sometimes days, and the data remains vulnerable during that window.

- Cost increases quickly. Redundancy means buying more drives than you actually use.

- Incorrect rebuilding, replacing a drive in the wrong order, removing a healthy drive, any of these can destroy the array’s structure and cause data loss.

RAID and Data Backup with Recovery

A RAID array protects you from certain problems, but it does not replace a proper backup. This is the part many users misunderstand. When everything runs smoothly, RAID gives you redundancy, keeps your system online, and prevents downtime. But if the array becomes corrupted, multiple disks fail, or the RAID controller itself breaks, the array can collapse in a way no parity or mirroring can fix on its own.

This is why a real backup is still essential, even when you use RAID. If a system keeps regular backups, recovery is usually straightforward: restore the files from your backup target, rebuild the array if needed, and continue working as normal. Backups protect you from accidental deletion, formatting mistakes, malware, and logical errors.

If no backup exists, then recovering data becomes much harder. At that point, a RAID array stops acting like a safety net and turns into a problem that requires specialized tools. You’ll need RAID data-recovery software that can reconstruct the array layout, detect the correct block size, interpret parity, and rebuild missing fragments before it can even attempt to restore your data. We put together a list of the best RAID data-recovery tools you can check out if you ever face this situation.

And since not everyone feels comfortable repairing a broken RAID at home, there’s always the option to send the disks to a professional data recovery lab. They can handle severe mechanical or logical damage, but the expertise comes with a price (a high one).

The Future of RAID

And to wrap up this post, let’s look ahead. We’ve already covered most of what a reader actually needs to know about RAID arrays. But RAID isn’t disappearing, it’s shifting into a slightly different role than the one it had twenty years ago.

The classic RAID setups (RAID 0/1/5/6/10) still appear in servers and RAID array storage units, but the industry is moving toward smarter, software-defined solutions. Traditional hardware RAID is slowly losing ground to systems that rely on intelligent storage layers rather than fixed controllers. You can already see this trend in technologies like ZFS, Btrfs, Microsoft Storage Spaces, Synology Hybrid RAID, and enterprise SDS platforms. They borrow the best RAID concepts but add automatic healing, built-in checksums, better parity handling, and real-time integrity verification.

Another ongoing shift is capacity. With today’s 20 TB-30 TB drives, a single disk failure puts enormous pressure on the array. Because of that, storage vendors push toward RAID-like redundancy built into the file system itself, not bolted on top. Erasure coding, multi-dimensional parity, and distributed storage clusters now take over tasks that once belonged exclusively to RAID controllers.

So will RAID disappear? Probably not. But it will keep evolving into something quieter in the background – a component of a larger storage architecture rather than the star of the show. For small office servers, NAS boxes, and home labs, RAID remains practical. For enterprise systems, the future leans toward flexible, self-healing file systems and smarter redundancy models that address problems RAID was never built to solve.

FAQs

- JBOD (Just a Bunch of Disks) combines drives without striping, mirroring, or parity. The disks stay independent, and the system simply treats them as one large pool. There’s no redundancy - if one disk fails, the data on that disk is gone, but it’s flexible and easy to expand.

- JBOF (Just a Bunch of Flash) follows the same idea but uses SSDs instead of HDDs. It’s common in servers and high-performance storage setups where fast flash drives act as a large, direct-attached storage pool. Both JBOD and JBOF differ from RAID because they offer capacity and simplicity, not redundancy or performance boosts.

7 Data Recovery

7 Data Recovery